Shot at Dawn

The weather alternated between sunshine and rain, and not just a sprinkle or a few rays. For half an hour we would don jackets and huddle under an umbrella or take cover from a dense, black cloud that covered a goodly part of the sky. Then, suddenly, blue sky would appear for half an hour where sunglasses came out, and jackets came off. In some ways this provided an ideal environment to explore the 150 acre National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire. It causes one to move differently through the monuments and to pause and read inscriptions

Making use of the tram that shuttles visitors around the arboretum, we had just remounted the tram in the South side as it started to rain. Moving slowly amongst the monuments was a comfortable way to observe monuments from the dry with the added benefit of listening to the docent’s description of each monument. At the east end stop, because of the rain, we elected to stay on the tram. As the docent began to describe the monument “Shot at Dawn”, I perked up and looked around for it, but, with so many monuments in sight, was not sure which one he was describing. Shot at Dawn memorializes soldiers who were shot “for cowardice” by his own men. I was somewhat dismayed by my inability to see the monument or to relate anything to the docent’s words. By the time we had gone another quarter mile, the bright sunshine was out again, and we had reached the sprawling Armed Services Memorial, an amazing memorial with many interesting and moving features. By now I had seen so many other monuments that I had forgotten about Shot At Dawn.

After spending some time at the Armed Services Memorial we walked the kilometer back to the visitor’s center and stopped in for a well earned cup of tea. The tea shop has a nice view of the arboretum and is a perfect place for a solemn discussion of our various reactions to different monuments. That is when I asked if anyone had seen the Shot At Dawn memorial described by the docent explaining that I had looked in every direction but was unable to see anything like he was describing. And so began a strange series of synchronicities. Each person had strained but failed to see it and had wished we had braved the rain to leave the tram on the east sector stop.

Ken had been to the arboretum several times, but realized that he had never seen this particular monument. When he ask me if I would be interested in walking back to it, I was not sure if he was, humoring me, if he was serious, testing me, or just being nice in trying to please his guests.

“It’s okay,” I responded. “I have seen many powerful monuments today, so missing this one is not a calamity.” But then I sensed more than an attempt simply to accommodate me.

“If you are really interested, then I would be happy to walk back with you to see it,” I admitted, unable to disguise some special calling I was beginning to feel.

“Let’s go while the sun is still shining,” he replied, grabbing his umbrella just in case. Pauline and Jane were happy to continue their enjoyment of the tea shop as we set out to backtrack on the tour. We quickly realized that we could cut the distance by crossing some of the fields, although miniature lakes had formed in a few of the lower areas.

When we arrived at the memorial, we discovered that, being behind a clump of trees, the monument was not visible from the tram, explaining why none of us had seen it. As we approached it we were alone. I got my first detailed description by reading the plaque at the monument.

Most of us have at least a vague idea of the atrocities of WWI and its seemingly purposeless waste of so many lives. The human toll in England as well as other countries was much greater than any other war. Enter any English village and you will find monuments listing those killed in action in the various wars, usually side by side. Especially in the small villages, where a dozen homes comprise the village, I was shocked to see thirty to fifty names listed for WWI, and usually a much smaller number for WWII.

WWI was characterized by many unusual factors. Without going so much into what seems today like ridiculous politics, people were so enthusiastic to join in the fight that may kids as young as 14 lied about their ages to be accepted. The official “legal” age was 17, but everyone knew that the force included thousands of under age “patriots” eager to get into the fight.

The front lines were characterized by bloodbaths where many thousands of men fought from trenches and stood knee deep in mud while artillery shells landed all around and the enemy were tunneling under the trenches to set off explosions. At regular intervals they were ordered to leave the trench and charge across open fields into a wall of lead and steel from machine guns. In many battles a battalion could be so shot up and isolated that complete confusion would set in. With explosions blowing body parts everywhere and German troops advancing, a shell shocked, poorly trained kid was expected to sit tight and act rationally. Some headed for the nearest cover in the woods, many ran until they got lost, some being completely confused and frightened and unable to do anything meaningful or even find their way back to their company.

Nevertheless, when roll call came, and a soldier did not respond, he was said to be absent without leave, and the officer in charge could hold a tribunal on the spot to punish anyone who had not behaved to his standard during the battle. If anyone was deemed to have acted cowardly, he could be executed by firing squad, the next day, all without legal defense, representation, or even a friend’s defense. This took place in many instances, specifically 306 executions, most of whom were kids, for desertion or for being a coward.

The monument clearly characterizes those who were executed. The majority are privates, 17-19 years old. The sculpture is extremely moving, a frightened 17 year old, blindfolded kid soldier, Herbert Francis Burden, standing with hands tied behind him waiting for the moment. Behind him are 306 posts representing the others who met the same fate. Facing the sculpture is a line of six trees, representing the firing squad. As Ken and I walked amongst the posts reading names, ranks, and ages, we were filled with questions. How could this be? Why do many have “unknown” written by their ages? Where was Herbert Francis Burden’s post? What was the medal hanging about the his neck? Why was he wearing an overcoat? Why did the public fail to act to stop this horrible practice? What actually happened in each case? I vowed to do more research when I got before a computer.

I wasn’t ready to leave the monument. There was more to be felt. “I want to be with this memorial a bit longer and sketch this monument,” I told Ken, who seemed to be having similar feelings. We took seats in benches conveniently placed by a competent designer, who would realize that many people would want to sit and contemplate more of its meaning

.As my sketch began emerging, a docent and an elderly gentleman approached the monument. The docent began describing the details of the monument to the gentleman. As I sketched I could not help but benefit from his descriptions which were answering all of the questions that Ken and I had been asking. The medal hanging about his neck was a target for the firing squad. The overcoat was one last gesture of kindness to protect the soldier from the chill. The missing ages on the posts were most likely missing because the soldiers were younger than the legal age of 17. Francis, himself, had enlisted at 15 and had managed to survive several campaigns before the one in which he was deemed cowardly. The docent explained that the justification for the execution was to prepare men psychologically for the next charge, simply an example, and these more frequently occurred shortly before a charge was planned.

The docent had answered all of my questions, save one-Where was Francis’ post? I thought I had searched all of the posts without finding his. So I approached him and asked him if he knew. He did not know, but he was not prepared to stop with that response.

“I should know that.”

He reached for his mobile phone and called the front desk. There was no answer, so he left a message. “This is Carl, and I am at the Shot At Dawn Exhibit, and I have a question? Where is the post of Herbert Francis Burden? Please call me as soon as you get this message.”

At that moment, a previously unnoticed lady who had just wandered among the posts, called out to us. “Did you say ‘Francis Burden’? His post is right here beside me?”

I often speak of coincidences in my experience of life, where the universe seems to provide me with all the answers to questions I have when working on a project. This is my sign that I am in harmony with the universe, and I must accept and put such information to use to insure that it continues.

The signs are always there when I take care to anticipate and stay open to observe. As I walked away from the memorial, I recalled that the number of soldiers, 306, the address where I grew up as a child. It adds up to nine, which comprises three 3’s, the number I use as a sign.

The Post Memorializing Private Herbert Francis Burden, a Soldier Who Was Shot at Dawn

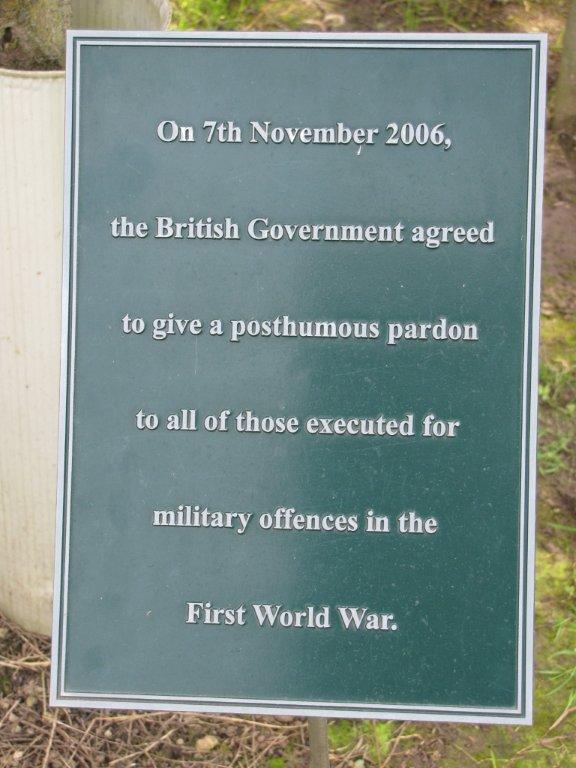

After the war, the records describing the details of the actions taken with 306 men were sealed, not to be opened until the year 2018. They simply had a record of being executed for cowardice in action or absent without leave, implying that these men had received a fair trial. Nevertheless, somehow this activity came to light earlier than that, giving rise to a group that called themselves the SAD (Shot At Dawn) group, whose goal was to get pardons for all of these men. Considering the facts, it should have been a no-brainer, but it was not, and a long hard battle took years to win. The arguments disclosed events that were extremely embarrassing to the military. In many instances the public began questioning why certain men who had been decorated for heroism had not instead been tried for war crimes. The actions, even of some of the top generals, came under question. Eventually, SAD prevailed and the British government pardoned the 306.

The British Government, under great pressure from the public, pardoned all of the 306.

Events such as these lead us to question many of the so-called truths that we are offered each day. This situation from today’s perspective is so easy to judge. Why was it so hard then? What similar things are routinely taking place today that will be so harshly judged a century from now?

t